Industry

The first industry in Highspire predates the development of the town. In 1775, John Hollingsworth erected a grist mill just upstream from Tinian. The mill consisted of a two-and-a-half-story red sandstone building with an overshot water wheel along Laurel Run, aka Mill Run and Buser Run. The first official map of Pennsylvania after independence, the 1792 Reading Howell Map, shows a grist mill on Mill Run within the future boundaries of Highspire.

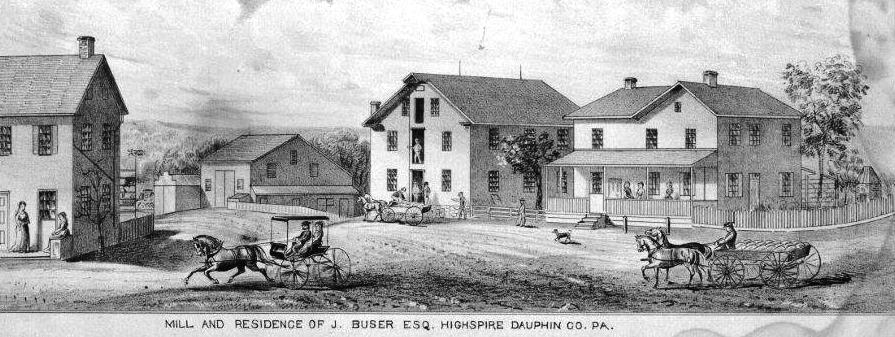

The mill changed hands several times over its first 85 years. It was destroyed by fire on March 3, 1860. The remains of the mill were purchased by John K. and Elizabeth Buser on Oct. 3, 1862. John Buser erected the present mill building with stone basement. The mill stayed in the Buser family until it was sold to John C. Kunkel of Harrisburg soon after the start of the 20th century.

The mill changed hands several times over its first 85 years. It was destroyed by fire on March 3, 1860. The remains of the mill were purchased by John K. and Elizabeth Buser on Oct. 3, 1862. John Buser erected the present mill building with stone basement. The mill stayed in the Buser family until it was sold to John C. Kunkel of Harrisburg soon after the start of the 20th century.

This is the Highspire grist mill as it looked in the late 19th Century when owned by John Buser.

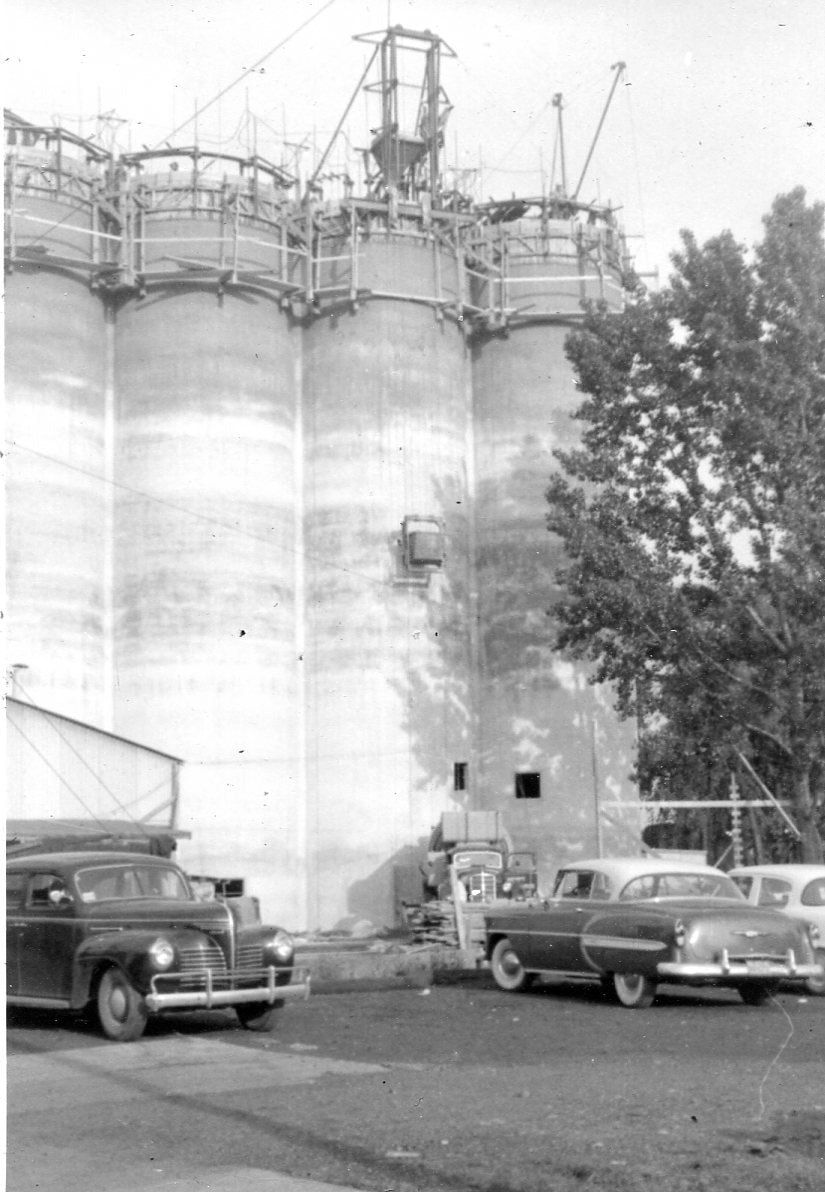

The last private owner was Henry Woolcott. In 1915, he took over management of the mill and purchased it in 1918. In 1920, Woolcott took the business public as Highspire Flour Mills Inc. and served as president and general manager. The capital raised by the public offering enabled a major expansion. In addition to new milling equipment, a concrete-lined channel was built through the plant for Laurel Run and 100,000-bushel, reinforced-concrete grain storage silos were built on the south side of Jury Street. Capacity was increased more than sevenfold. On Jan. 23, 1928, the Wheatena Corp. acquired Highspire Flour Mills. The mill would operate as a subsidiary of Wheatena for the next 37 years. During that period it was managed by Warren Harlacher, Henry Woolcott’s son-in-law.

The last expansion of the mill was the construction of the large concrete silos in 1955

In November 1965, the Standard Milling Co., a subsidiary of the Kansas City, MO-based Uhlmann Co., purchased the Wheatena Corp. and Highspire Flour Mills. In 1967, production of Wheatena cereal was moved to the Highspire plant. The cereal brand changed hands several times in the late 20th century. In 2001, Homestat Farm Ltd., a small business specializing in all-natural, nutritious vintage brands, bought the cereal manufacturing portion of the plant and the cereal brands Wheatena, Maypo and Maltex. Homestat Farm still manufactures those brands at their plant adjacent to the mill at 201 Race St. The mill itself is no longer in use.

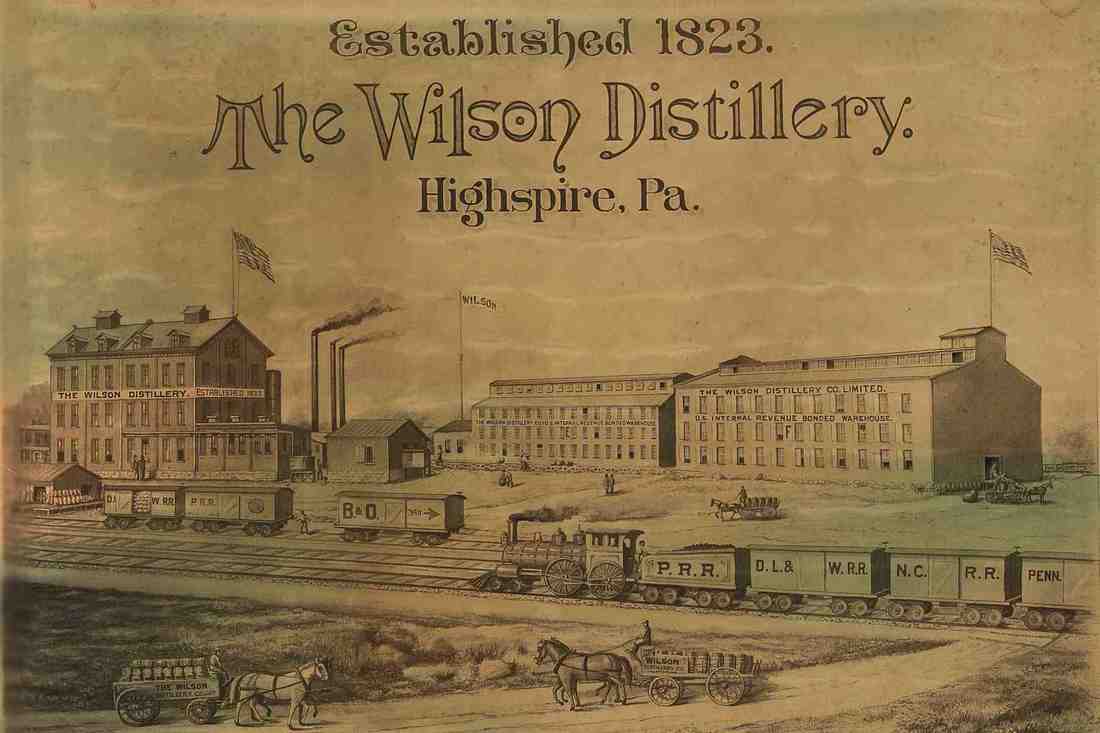

The most famous industry in the history of Highspire was the Wilson Distillery, which was started in 1823 by an Irish immigrant named Robert Wilson. He operated the distillery until 1870.

This illustration depicts the Wilson Distillery in the late 19th Century after it had been acquired by the Goldsborough family and greatly expanded, but before the brand name was changed to Highspire.

Wilson developed a formula for making pure rye whiskey that became very popular. Wilson’s son William K. Wilson eventually sold the distillery. After changing hands several times it was acquired by the Goldsborough family of Baltimore. They greatly expanded the operation and changed the name to the Highspire Distilling Co., and the brand name to Highspire Whiskey around the turn of the 20th Century. It was sold throughout the U.S., the Western Hemisphere and Europe. In the early 1900s, the distillery had a capacity of 7,000 to 9,000 barrels per year and had a warehouse that could store more than 50,000 barrels. Highspire Pure Rye Whiskey spread the name Highspire through much of the developed world.

The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, instituting prohibition, brought this industry to an end in Highspire.

The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, instituting prohibition, brought this industry to an end in Highspire.

In the late 19th Century the area just east of Lumber Street developed into an industrial area. Distiller Robert Wilson's sons Henry and William were involved in several other commercial enterprises in this area. They built a saw mill with a large log pond, where the Memorial Park baseball field is located today. There they made railroad ties for the B&O Railroad and built canal boats. They also built a railroad car manufacturing plant on the east side of Lumber Street between Lusk Avenue and the railroad tracks.

In this 1973 Bird's Eye View illustration of the Lumber Street industrial area at the east end of Highspire, the yellow arrows point to #3, the Wilson Distillery; #4, the railroad car manufacturing plant; and #5, the saw mill.

Another late-19th century industry at the end of Lumber St. on the banks of the Susquehanna was the Highspire Glue Works, established in 1884. It was located just west of Burd Run. The glue works was in business for only 20 years. In 1904, an ice jam on the river caused the water level to rise rapidly, and large, thick chunks of ice spilled over the river banks. The glue factory was badly damaged by the ice, and the plant was razed soon after the flood.

Highspire Glue Works

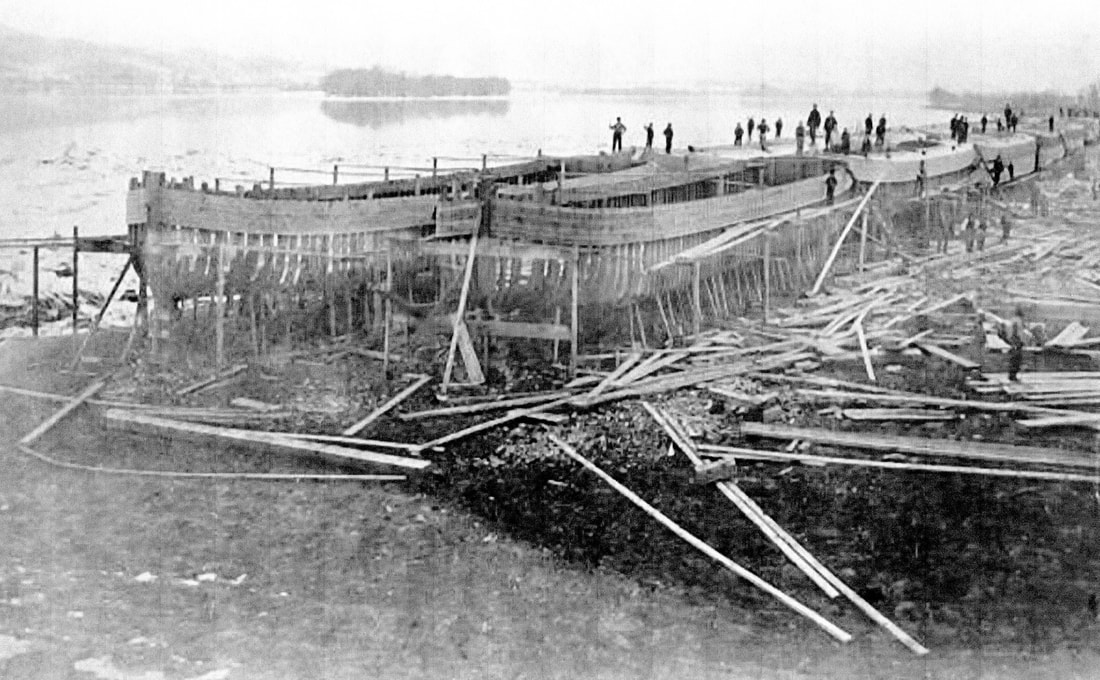

In addition to the boat building operation of the Wilson enterprise previously mentioned, there was a large canal boat building operation along the river. William Frick had a boat yard that employed many craftsmen in the construction of canal boats. Surprisingly, the boats were not built for the Pennsylvania Canal, but rather for the Schuylkill Canal in eastern Pennsylvania. The boats would have been floated down the river and entered the Union Canal at Middletown for transport on to the Schuylkill Canal at Reading.

Frick Boat Yard

There also were several cigar-making businesses in Highspire in the late 19th century. Archie Bowers built a cigar factory along the south side of Jury Street just west of the flour mill. When that didn’t provide the profits Bowers hoped for, he opened a shirt factory in the same location. The shirt factory wasn’t a financial success either, so Bowers converted the building to private dwellings. This row of houses became known as Shirt Factory Row. Another maker of handmade cigars was Alfred Cannon, who had a shop at the corner of Front and Railroad streets. He used an acid to make a white trademark on his cigars which also was supposed to improve their flavor.

After the distillery closed, the Highspire Knitting Co. used the main distillery building as a manufacturing facility to produce stockings in the 1920s and 1930s and became a major employer in the borough. The knitting mill closed in 1937.

In June 1922, Keystone Carbonic Gas purchased land just east of Burd Run on the south side of Second Street for the construction of a carbonic gas (carbon dioxide) manufacturing plant. The primary use of carbonic gas was to produce the fizz in bottled and soda fountain drinks. The Highspire plant was located to serve Central Pennsylvania. In less than two years the company went into receivership due to embezzlement by company officers. The plant then was purchased by Fred S. Davis. Under his leadership, the Highspire plant became a pioneer in the dry ice business. In 1930, Davis sold the company to Liquid Carbonic Corp., the world’s largest producer of carbonic gas, soda machinery and bottlers’ goods. Liquid Carbonic ceased production at the Highspire plant in the 1930s. The building is currently is occupied by Dempsey Uniform and Linen Supply.

A Highspire manufacturer still fondly remembered by older residents past and present is Zeller’s Potato Chips. Paul and Cora Zeller moved to Highspire in 1918. They started making potato chips after Paul was laid off from the Steelton steel mill in 1921. Their chips were of excellent quality, fried in peanut oil. The Zellers had to hustle in the early years to build their business, but by the end of the decade they had a solid enterprise with a product of excellent quality and loyal employees. They weathered the Great Depression and continued to expand through the 1940s and 1950s. The factory was located beside the Zellers’ home on the west end of Eshleman Street.

Paul Zeller turned the business over to son-in-law Jack Palmer in the late 1950s. After a flood destroyed the potato inventory in the early 1960s, Mr. Palmer decided to get out of the chip business and sold it to a New York company. The new owners reduced the quality of the product in an effort to save money. They also lost many long-time Zeller’s employees. Much to Paul Zeller’s disappointment, the business closed soon after being sold.

Although not a manufacturing enterprise, one of the oldest industrial operations in Highspire today is the Highspire Log Yard of Bommer Geesaman Co. Inc. Established in 1972, it specializes in the wholesale distribution of high-grade Appalachian hardwood saw logs and veneer logs. From its location along the south end of Lumber Street, it serves both domestic and foreign markets and can containerize logs for port delivery.

After the distillery closed, the Highspire Knitting Co. used the main distillery building as a manufacturing facility to produce stockings in the 1920s and 1930s and became a major employer in the borough. The knitting mill closed in 1937.

In June 1922, Keystone Carbonic Gas purchased land just east of Burd Run on the south side of Second Street for the construction of a carbonic gas (carbon dioxide) manufacturing plant. The primary use of carbonic gas was to produce the fizz in bottled and soda fountain drinks. The Highspire plant was located to serve Central Pennsylvania. In less than two years the company went into receivership due to embezzlement by company officers. The plant then was purchased by Fred S. Davis. Under his leadership, the Highspire plant became a pioneer in the dry ice business. In 1930, Davis sold the company to Liquid Carbonic Corp., the world’s largest producer of carbonic gas, soda machinery and bottlers’ goods. Liquid Carbonic ceased production at the Highspire plant in the 1930s. The building is currently is occupied by Dempsey Uniform and Linen Supply.

A Highspire manufacturer still fondly remembered by older residents past and present is Zeller’s Potato Chips. Paul and Cora Zeller moved to Highspire in 1918. They started making potato chips after Paul was laid off from the Steelton steel mill in 1921. Their chips were of excellent quality, fried in peanut oil. The Zellers had to hustle in the early years to build their business, but by the end of the decade they had a solid enterprise with a product of excellent quality and loyal employees. They weathered the Great Depression and continued to expand through the 1940s and 1950s. The factory was located beside the Zellers’ home on the west end of Eshleman Street.

Paul Zeller turned the business over to son-in-law Jack Palmer in the late 1950s. After a flood destroyed the potato inventory in the early 1960s, Mr. Palmer decided to get out of the chip business and sold it to a New York company. The new owners reduced the quality of the product in an effort to save money. They also lost many long-time Zeller’s employees. Much to Paul Zeller’s disappointment, the business closed soon after being sold.

Although not a manufacturing enterprise, one of the oldest industrial operations in Highspire today is the Highspire Log Yard of Bommer Geesaman Co. Inc. Established in 1972, it specializes in the wholesale distribution of high-grade Appalachian hardwood saw logs and veneer logs. From its location along the south end of Lumber Street, it serves both domestic and foreign markets and can containerize logs for port delivery.